The economy of Africa consists of the trade, industry, agriculture, and human resources of the continent. As of 2012, approximately 1.07 billion people[2] were living in 54 different countries in Africa. Africa is a resource-rich continent.[3][4]Recent growth has been due to growth in sales in commodities, services, and manufacturing.[5] Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, is expected to reach a GDP of $29 trillion by 2050.[6]

In March 2013, Africa was identified as the world's poorest inhabited continent; however, the World Bank expects that most African countries will reach "middle income" status (defined as at least US$1,000 per person a year) by 2025 if current growth rates continue.[7] In 2013, Africa was the world’s fastest-growing continent at 5.6% a year, and GDP is expected to rise by an average of over 6% a year between 2013 and 2023.[3][8] Growth has been present throughout the continent, with over one-third of Sub-Saharan African countries posting 6% or higher growth rates, and another 40% growing between 4% to 6% per year.[3] Several international business observers have also named Africa as the future economic growth engine of the world.[9]

A large literature in economics and political science has developed to explain this “resource curse,” and civil-society groups (such as Revenue Watch and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative) have been established to try to counter it. Three of the curse’s economic ingredients are well known:

Resource-rich countries tend to have strong currencies, which impede other exports;

Because resource extraction often entails little job creation, unemployment rises;

Volatile resource prices cause growth to be unstable, aided by international banks that rush in when commodity prices are high and rush out in the downturns (reflecting the time-honored principle that bankers lend only to those who do not need their money).

Moreover, resource-rich countries often do not pursue sustainable growth strategies. They fail to recognize that if they do not reinvest their resource wealth into productive investments above ground, they are actually becoming poorer. Political dysfunction exacerbates the problem, as conflict over access to resource rents gives rise to corrupt and undemocratic governments

A teacher of history while teaching on class distinction said, "the rich need the poor in order to be rich" and then proceeded to say that "Africa does not deserve to be rich and neither do Africans". You can know one thing, this old man that fought with my African people, laid down his own life to fight for our freedom was not happy about such teaching in a school. As I said to our people all before as there is a GOD, only bad people teach the wrong things through. Truth is change happens from you, just because you are not taught it right does not mean you need to move the same evils through. That when you do see from history, they have been robbed, enslaved, tortured, the worst kind of human atrocities done to them for what reason? That same has been done too many different races through leaders who believe they are just some supreme dictators over others’ lives.

Resource-rich countries tend to have strong currencies, which impede other exports;

Because resource extraction often entails little job creation, unemployment rises;

Volatile resource prices cause growth to be unstable, aided by international banks that rush in when commodity prices are high and rush out in the downturns (reflecting the time-honored principle that bankers lend only to those who do not need their money).

Moreover, resource-rich countries often do not pursue sustainable growth strategies. They fail to recognize that if they do not reinvest their resource wealth into productive investments above ground, they are actually becoming poorer. Political dysfunction exacerbates the problem, as conflict over access to resource rents gives rise to corrupt and undemocratic governments

A teacher of history while teaching on class distinction said, "the rich need the poor in order to be rich" and then proceeded to say that "Africa does not deserve to be rich and neither do Africans". You can know one thing, this old man that fought with my African people, laid down his own life to fight for our freedom was not happy about such teaching in a school. As I said to our people all before as there is a GOD, only bad people teach the wrong things through. Truth is change happens from you, just because you are not taught it right does not mean you need to move the same evils through. That when you do see from history, they have been robbed, enslaved, tortured, the worst kind of human atrocities done to them for what reason? That same has been done too many different races through leaders who believe they are just some supreme dictators over others’ lives.

Africa's economy was diverse, driven by extensive trade routes that developed between cities and kingdoms. Some trade routes were overland, some involved navigating rivers, still others developed around port cities. Large African empires became wealthy due to their trade networks, for example Ancient Egypt, Nubia, Mali, Ashanti, and the Oyo Empire.

Some parts of Africa had close trade relationships with Arab kingdoms, and by the time of the Ottoman Empire, Africans had begun converting to Islam in large numbers. This development, along with the economic potential in finding a trade route to the Indian Ocean, brought the Portuguese to sub-Saharan Africa as an imperial force. Colonial interests created new industries to feed European appetites for goods such as palm oil, rubber, cotton, precious metals, spices and other goods.

Following the independence of African countries during the 20th century, economic, political and social upheaval consumed much of the continent. An economic rebound among some countries has been evident in recent years, however.

The dawn of the African economic boom (which is in place since 2000's) was similar to the Chinese economic boom that had emerged in Asia since late 1970's. Currently, South Africa and Nigeria ranks among the continent's largest economies, with Egypt economically scrambling and suffering from the recent political turmoil. Equatorial Guinea possessed Africa's highest GDP per capita albeit allegations of human rights violations. Oil-rich countries such as Algeria, Libya and Gabon, and mineral-rich Botswana emerged among the top economies since the 21st century, while Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo, potentially among the world's richest nations, have sunk into the list of the world's poorest nations due to pervasive political corruption, warfare and braindrain of workforce. Botswana remains the site of Africa's longest and one of the world's longest periods of economic boom (1966–1999).

Current conditions[edit]

In the past ten years, growth in Africa has surpassed that of East Asia[10] Data suggest parts of the continent are now experiencing fast growth, thanks to their resources and increasing political stability and 'has steadily increased levels of peacefulness since 2007'. The World Bank reports the economy of Sub-Saharan African countries grew at rates that match or surpass global rates.[11][12]

The economies of the fastest growing African nations experienced growth significantly above the global average rates. The top nations in 2007 include Mauritania with growth at 19.8%, Angola at 17.6%, Sudan at 9.6%, Mozambique at 7.9% and Malawi at 7.8%.[13] Other fast growers include Rwanda, Mozambique, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia. Nonetheless, growth has been dismal, negative or sluggish in many parts of Africa including Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo and Burundi. Many international agencies are increasingly interested in investing in emerging African economies.[14] especially as Africa continues to maintain high economic growth despite current global economic recession.[15] The rate of return on investment in Africa is currently the highest in the developing world.[16]

Debt relief is being addressed by some international institutions in the interests of supporting economic development in Africa. In 1996, the UN sponsored the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, subsequently taken up by the IMF, World Bank and the African Development Fund (AfDF) in the form of the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). As of 2013, the initiative has given partial debt relief to 30 African countries.[17]

Trade growth[edit]

Trade has driven much of the growth in Africa's economy in the early 21st century. China and India are increasingly important trade partners; 12.5% of Africa's exports are to China, and 4% are to India, which accounts for 5% of China's imports and 8% of India's. The Group of Five (Indonesia, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates) are another increasingly important market for Africa's exports.[18]

Future[edit]

Africa's economy—with expanding trade, English language skills (official in many Sub-Saharan countries), improving literacy and education, availability of splendid resources and cheaper labour force—is expected to continue to perform better into the future. Trade between Africa and China stood at US$166 billion in 2011.[19]

Africa will experience a "demographic dividend" by 2035, when its young and growing labour force will have fewer children and retired people as dependents as a proportion of the population, making it more demographically comparable to the US and Europe.[20] It is becoming a more educated labour force, with nearly half expected to have some secondary-level education by 2020. A consumer class is also emerging in Africa and is expected to keep booming. Africa has around 90 million people with household incomes exceeding $5,000, meaning that they can direct more than half of their income towards discretionary spending rather than necessities. This number could reach a projected 128 million by 2020.[20]

During the President of the United States Barack Obama's visit to Africa in July 2013, he announced a US$7 billion plan to further develop infrastructure and work more intensively with African heads of state. A new program named Trade Africa, designed to boost trade within the continent as well as between Africa and the U.S., was also unveiled by Obama.[21]

Causes of the economic underdevelopment over the years[edit]

The seemingly intractable nature of Africa's poverty has led to debate concerning its root causes. Endemic warfare and unrest, widespread corruption, and despotic regimes are both causes and effects of the continued economic problems. The decolonization of Africa was fraught with instability aggravated by cold war conflict. Since the mid-20th century, the Cold War and increased corruption and despotism have also contributed to Africa's poor economy.

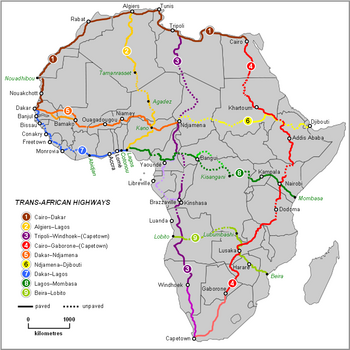

Infrastructure[edit]

According to researchers at the Overseas Development Institute, the lack of infrastructure in many developing countries represents one of the most significant limitations to economic growth and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).[22] Infrastructure investments and maintenance can be very expensive, especially in such areas as landlocked, rural and sparsely populated countries in Africa.[22]

It has been argued that infrastructure investments contributed to more than half of Africa's improved growth performance between 1990 and 2005 and increased investment is necessary to maintain growth and tackle poverty.[22] The returns to investment in infrastructure are very significant, with on average 30–40% returns for telecommunications (ICT) investments, over 40% for electricity generation, and 80% for roads.[22]

In Africa, it is argued that to meet the MDGs by 2015, infrastructure investments would need to reach about 15% of GDP (around $93 billion a year).[22] Currently, the source of financing varies significantly across sectors.[22] Some sectors are dominated by state spending, others by overseas development aid (ODA) and yet others by private investors.[22] In sub-Saharan Africa, the state spends around $9.4 billion out of a total of $24.9 billion.[22]

In irrigation, SSA states represent almost all spending; in transport and energy a majority of investment is state spending; in Information and communication technologies and water supply and sanitation, the private sector represents the majority of capital expenditure.[22] Overall, aid, the private sector and non-OECD financiers between them exceed state spending.[22] The private sector spending alone equals state capital expenditure, though the majority is focused on ICT infrastructure investments.[22] External financing increased from $7 billion (2002) to $27 billion (2009). China, in particular, has emerged as an important investor.[22]

Colonialism[edit]

Main article: Colonisation of Africa

The economic impact of the colonization of Africa has been debated. In this matter, the opinions are biased between researchers, some of them consider that Europeans had a positive impact on Africa; others affirm that Africa's development was slowed down by colonial rule.[23] The principal aim of colonial rule in Africa by European colonial powers was to exploit natural wealth in the African continent at a low cost. Some writers, such as Walter Rodney in his book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, argue that these colonial policies are directly responsible for many of Africa's modern problems. Critics of colonialism charge colonial rule with injuring African pride, self-worth and belief in themselves. Other post-colonial scholars, most notably Frantz Fanon continuing along this line, have argued that the true effects of colonialism are psychological and that domination by a foreign power creates a lasting sense of inferiority and subjugation that creates a barrier to growth and innovation. Such arguments posit that a new generation of Africans free of colonial thought and mindset is emerging and that this is driving economic transformation.[24]

Historians L. H. Gann and Peter Duignan have argued that Africa probably benefited from colonialism on balance. Although it had its faults, colonialism was probably "one of the most efficacious engines for cultural diffusion in world history".[25] These views, however, are controversial and are rejected by some who, on balance, see colonialism as bad. The economic historian David Kenneth Fieldhouse has taken a kind of middle position, arguing that the effects of colonialism were actually limited and their main weakness wasn't in deliberate underdevelopment but in what it failed to do.[26] Niall Ferguson agrees with his last point, arguing that colonialism's main weaknesses were sins of omission.[27] Analysis of the economies of African states finds that independent states such as Liberia and Ethiopia did not have better economic performance than their post-colonial counterparts. In particular the economic performance of former British colonies was better than both independent states and former French colonies.[28]

Africa's relative poverty predates colonialism. Jared Diamond argues in Guns, Germs, and Steel that Africa has always been poor due to a number of ecological factors affecting historical development. These factors include low population density, lack of domesticated livestock and plants and the North-South orientation of Africa's geography.[29] However Diamond's theories have been criticized by some including James Morris Blaut as a form of environmental determinism.[30] Historian John K. Thornton argues that sub-Saharan Africa was relatively wealthy and technologically advanced until at least the seventeenth century.[31] Some scholars who believe that Africa was generally poorer than the rest of the world throughout its history make exceptions for certain parts of Africa. Acemoglue and Robinson, for example, argue that most of Africa has always been relatively poor, but "Aksum, Ghana, Songhay, Mali, [and] Great Zimbabwe... were probably as developed as their contemporaries anywhere in the world."[32] A number of people including Rodney and Joseph E. Inikori have argued that the poverty of Africa at the onset of the colonial period was principally due to the demographic loss associated with the slave trade as well as other related societal shifts.[33] Others such as J. D. Fage and David Eltis have rejected this view.[34]

Language diversity[edit]

African countries suffer from communication difficulties caused by language diversity. Greenberg's diversity index is the chance that two randomly selected people would have different mother tongues. Out of the most diverse 25 countries according to this index, 18 (72%) are African.[35] This includes 12 countries for which Greenberg's diversity index exceeds 0.9, meaning that a pair of randomly selected people will have less than 10% chance of having the same mother tongue. However, the primary language of government, political debate, academic discourse, and administration is often the language of the former colonial powers; English, French, or Portuguese.

Trade based theories[edit]

Dependency theory asserts that the wealth and prosperity of the superpowers and their allies in Europe, North America and East Asia is dependent upon the poverty of the rest of the world, including Africa. Economists who subscribe to this theory believe that poorer regions must break their trading ties with the developed world in order to prosper.[36]

Less radical theories suggest that economic protectionism in developed countries hampers Africa's growth. When developing countries have harvested agricultural produce at low cost, they generally do not export as much as would be expected. Abundant farm subsidies and high import tariffs in the developed world, most notably those set by Japan, the European Union's Common Agricultural Policy, and the United States Department of Agriculture, are thought to be the cause. Although these subsidies and tariffs have been gradually reduced, they remain high.

Local conditions also affect exports; state over-regulation in several African nations can prevent their own exports from becoming competitive. Research in Public Choice economics such as that of Jane Shaw suggest that protectionism operates in tandem with heavy State intervention combining to depress economic development. Farmers subject to import and export restrictions cater to localized markets, exposing them to higher market volatility and fewer opportunities. When subject to uncertain market conditions, farmers press for governmental intervention to suppress competition in their markets, resulting in competition being driven out of the market. As competition is driven out of the market, farmers innovate less and grow less food further undermining economic performance.[37][38]

No comments:

Post a Comment